the online notebook of Jonathan Mayhew

Somewhere in the synapse…

ALAN BUTLER & LOLA RAYNE BOOTH

In a recent essay, the artist Paul Chan describes his memory of the 1990-91 recession in the United States. He describes how everything around him changed, causing various things to happen; adjustments to society were made and then unmade, as life began to go back to 'normal'. Comparing our ideological belief in capitalism with the Spiritual, he reminds us that the term ‘recession’ also possesses Religious associations. A ‘recessional’ being “the time after church service when the clergy departs and the people who make up the congregation are left to themselves…. The end of the service announces the beginning of another kind of time: no more commands for sacrifice and expressions of faith; no more sermons from the book of Progress”. This is a satisfying comparison, because it suggests that a recession can offer us a positive moment; a time for reflection and consideration to where we have been and what we have seen and done, before we prepare ourselves for the inevitable violent attempt to progress our cultures forward once more.

It is this ‘recessional’ space, which is an interesting factor in Magnhild Opdøl’s work. Much of her past creations operated through détournement, sampling pop culture and the equally inspirational and oppressive force that is art history, to create new original works. It can be said that successful appropriations treat all cultures (and their produce) as information and part of an ever-evolving, pre-existing language. In appropriating, the artist does not necessarily need to subvert the original materials (in fact many appropriations perpetuate the nature of their sources), but sometimes the act of sampling is like stepping out of the realm of the maker and reflecting upon the meanings and supposed ‘truths’ which are given to us by history. Sampling could be seen as a ‘recessional’ space, free from authority and cultural dogma. The process of sampling - the re-appropriation of what came before- is analytical before it is creative and constructs a nebulous distinction between producer and consumer. Similarly, a time of crisis becomes a time of opportunity.

In her new exhibition, Opdøl’s works continue to echo the past. The past is a starting point, which once analysed and considered by the artist, is built upon and exploited to create new works. A series of small pencil studies of insects are the result of an investigation into pathology. Opdøl’s recurring theme of the cycle of life and death, lead her to create dozens of intricate pencil studies of insects of which can live in human corpses. The list of insects somewhat ‘appropriated’ from the practice of pathology, reveal information about the corpse itself. The pathologist can tell how long the host body has been dead judging from how many generations of egg/insect cycles have taken place. Opdøl’s investigations consider pre-existing information and knowledge, which are themselves an analytical process using pre-existing information and knowledge. This feedback cycle created by Opdøl’s choice of subject/process echoes not only the cycles of the insects, but the cycles which take place when appropriating ideas and applying new meanings or purposes upon them. It is not just in the act of sampling - or applying that sample to a remix - that her art exists, perhaps also there is that tiny synapse between the loops and cycles where Opdøl’s creativity occurs. This synapse contains the artist’s decisions - her creativity - and cements together the physical and the conceptual; a recessional space, which is hidden between subject matter and form.

The cycle also exists in her work ‘The Great Escape’. This taxidermy piece consists of a mouse and Opdøl’s (ex-)pet cat, which has spent the last few years posthumously ‘living’ in the artist’s freezer in Norway. Thawed out and taken to the taxidermy studio, the two animals now playfully co-exist in assiduous stasis. In an uncannily outré moment, the work depicts a mouse, post-gastric, yet unscathed, escaping from the cats anus. Ready to consume once more, the rotation of the startled cat’s head greets the mouse on his rebirth as if to repeat the event once again. It is that recessional moment, mirroring Opdøl’s appropriation in her process. ‘The Great Escape’ depicts that split moment, which is neither the beginning nor end of a cycle – not life nor death, that moment that simply bridges together the two and is just part of their recurring nature. In this way, the artists who work in the area of appropriation can be seen as coprophagic, where the used, found or discarded materials, within the recessional space, become food for thought. Once appropriated, they re-enter the domain for potential remix – part of a cycle where nothing can have definite meaning and is a breeding-ground for ambiguity. Her series of exquisite pencil drawings, which accompany the sculpture, investigate a moment where a cat is tearing apart a mouse, which may or may not be dead, re-iterate this.

The work in Opdøl’s new exhibition, moves away from ubiquitous appropriations and enters meta-physical realms. These works are exercises in exploring systems and cycles of life and death and consequently allow the viewer peer into that gap between the concept and the form where her creative decisions exist. Once these decisions made, they will cause various things to happen, such as ‘meaning’ to be formulated. Regardless of what ‘meaning’ you as a viewer discover, what is revealed in the artist’s process and produce is the relentlessness of these life/death cycles. They are merely part of nature. The artist will continue to appropriate the physical and meta-physical, a life in a sort of recessional stasis; a perpetual state of crisis or opportunity, depending which way you want to look at it.

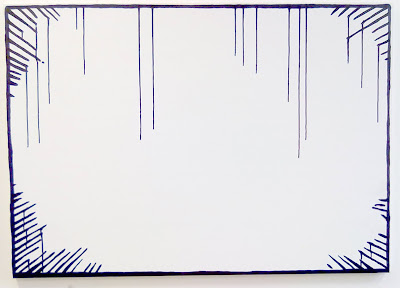

Team is pleased to present an exhibition of new drawings, alongside one sculpture, by the New York-based Banks Violette. The exhibition will run from the 7th of May through the 20th of June 2009. Team Gallery is located at 83 Grand Street, between Wooster and Greene, on the ground floor. Sculptor Banks Violette has always referred to his drawings as “film cells from the world’s slowest movie.” As with the cinema, meaning does not adhere solely to individual images but rather to their accretion over time. Viewed singly, these exquisitely rendered pictures seem miraculous transfigurations of realism, but when seen in groups they form a continuous landscape of memory, regret and melancholy. The iconography on which Violette built this show includes the ace of spades, a grinning skull from a B-movie campaign, a famous Vietnam-era image of human suffering, a roadside death shrine, discarded party balloons, a theater spotlight, and the Crimson Ghost from the 1940s Republic film serial. When taken together, the drawings touch on themes of redemption and faith, death and transformation. Central to the exhibition is a portrait of Bela Lugosi as Jesus Christ. Before coming to the U.S. to make his name as the cinema's most famous vampire, the Hungarian actor made his living playing the lead in passion plays. Violette’s Dracula/Christ manages to take the perceived goodness and suffering of the Jesus figure and "confuse" them with the monstrous evil that Lugosi would so successfully embody as the Count. Lugosi's well-documented drug addiction and late-period decline into poverty and obscurity are also clearly a part of what attracts Violette to this image. A seemingly benign religious portrait, in Violette’s hands, becomes a container for Hollywood’s lies, America’s morbid fascination with disposable celebrity, and our constant need to construct mythologies of total success and absolute failure. Violette’s drawings are also, at their very core, terribly American works of art, a fact foregrounded here by an eight by four foot drawing of the U.S. flag rendered in black and white and mounted onto a slab of aluminum which is then simply propped against the wall. This monolith helps underline the physicality of Violette’s drawings – images struggle to the surface from a dense mass of graphite applied sometimes laboriously and vigorously; sometimes with a gentle and persuasive sensitivity. The show’s lone sculpture is a motorcycle that has been cast entirely in resin and salt. The stark white presence will be paired with a drawing of a shrine left at a scene where someone had died in a motorcycle crash. The way in which the image has been rendered makes the drawing seem to appear and disappear as one looks at it. A very strange sense pervades that you are both looking at something specific and looking at nothing at all. Violette’s drawings are always coming together and falling apart in the eye of the spectator. Soft edges, hardened into image through cognition, vanish into nothingness and slip from legibility. Violette’s work, sometimes crushingly monumental and brutally hard-edged, always sopresent, is actually, delicately, about the “after” of things. It is not the photo-realistic clarity of the drawings that gives them their power but rather the way in which they remain vague and unreal impressions with a ghost-like presence. The commemorative and the evidentiary, posed as poetry and prose, have remained central in Violette’s work. The contradictory and the elusive are the continent of his travels. If one looks for the development in Violette’s work one finds a movement towards abstraction: from his earlier works, which sprang from specific social, usually criminal, phenomenon to his most recent investigations of staging and the spectacular as vessels of oblivion.

MICHAËL BORREMANS : Taking Turns @ David Zwirner

For the current show at David Zwirner, Borremans has created five new paintings and is presenting three films: The Feeding, The Storm, and Taking Turns.

For this exhibition, the gallery (519 West 19th Street) has been divided into two relatively equal spaces. Upon entering the first space, a 35mm film projector shows a loop of The Storm as a large-scale projection, reaching close to 15 feet in height and 23 feet in width on the gallery wall. In the film, three black men, wearing identical cream-colored uniforms (a mix of work clothes and stage costumes), are sitting slumped in chairs in the corner of a white, empty room. The harsh light of a naked bulb alters the shot by modifying the intensity of the shadows moving imperceptibly on the surface of the wall.1

The second gallery space introduces an intimate presentation of two other 35mm films, The Feeding and Taking Turns, both which have been transferred to DVDs and viewed within wall-mounted wooden frames. The films are shown alongside the exhibition’s five oil on canvas paintings: The Apron, Earthlight Room, The Load, The Load (II), The Load (III).

In The Feeding, the three figures from The Storm reappear, standing around enormous reams of white cardboard that give the impression of levitating above a table covered with a spotless cloth in the middle of a room.2 In Taking Turns, a woman holds the torso of a life-sized mannequin, and slowly moves and spins the torso on top of a horizontal surface. There is an ambiguity between what is real and what is artificial, as their two faces and figures overlap and rotate in the film’s frames. Once again, the theme of the double, or the doppelganger, is a device encountered throughout Borremans’ oeuvre.3

Formally and thematically, Borremans’ films are closely related to his two-dimensional work. They are shifting ‘tableaux vivants’ with poetic titles, in which the artist very gradually, with subtle camera work, creates an oppressive atmosphere. He uses a fixed camera position or deliberately zooms in on certain details of the scenery, body parts, faces, or clothing. With slight light-dark fluctuations, flowing edited shots or the repetition of certain actions, Borremans builds up a gripping but subdued suspense.